Beate C. Minkovski is the co-founder and executive director of Woman Made Gallery established in 1992. She was active with arts organizations Intuit and ARC, and served on the Community Arts Assistance Program (CAAP) Panel for the Chicago Cultural Center from 2005 to 2008, and in 2012. Minkovski was part of the Special Service Area (SSA) #29 Commission jury panel for public art in Chicago's West Town. She has curated exhibitions for various arts organizations, including the Women’s Caucus for Art, The Women's Art Registry of Minnesota, and The Art Center in Highland Park, Illinois. She is the 2006 CWCA award recipient for achievements in the arts. Originally from Bremen, Germany where she studied sculpture and ceramics, she came to the US in 1965, and earned a Bachelor of Arts at Northeastern Illinois University in 1992. She is married to Michael Minkovski and has five children and ten grandchildren.

Photo: Jennifer Bisbing

At the end of December 2014, Beate Minkovski will retire as Executive Director of Woman Made Gallery with a legacy of 22 years of love, sweat and tears; community activism and feminist strides; and launched careers and forever friendships. Under her direction WMG has become a staple in Chicago’s art community, the feminist community, and the world. In 2011 Today’s Chicago Woman named Minkovski one of ‘100 Women Making a Difference.’

At an age when most people are mid-career, Minkovski intrepidly launched hers. In a small storefront in Ravenswood Manor, Minkovski and business partner Kelly Hansen opened a gallery for women artists: they saw a need and took action.

WMG began as an art studio and quickly became a haven for artists, passersby and curious neighbors. For women artists it was a stepping stone, a platform for dialogue and networking, and an educational facility to elevate their professionalism. The gallery’s mission is ‘to support, cultivate and promote the diverse contributions of women in the arts through exhibitions and programs that serve, educate and enrich the community.’

An early adopter of technology, WMG boasted a world-wide web presence in the mid 1990’s. This gave them an edge and secured a prominent place in the art world at a time when there were only a handful of galleries dedicated to women artists individually, locally, and globally. Minkovski has fostered the careers of gallery directors and interns, advised and educated her boards, launched the careers of emerging artists, and has empowered and given a voice to many timid souls.

Under Minkovski’s enthusiastic leadership, more than 7,500 women artists have exhibited at the gallery. WMG has hosted 378 exhibitions, including group and solo shows, and an annual international juried exhibition that represents women artists from around the world. In 2012 to foster community between neighborhoods that lack ready access to arts programming, WMG launched 20 Neighborhhoods Project, a series of art and educational workshops.

What are your Chicago roots?

I don’t have roots here—I was born somewhere else. But I have lived here longer than anywhere else in the world, and I would not want to leave. I created roots for my five children.

What did you want to be when you were 13?

I always wanted to be an artist.

What inspired you to study art at NEIU?

NEIU had lots of older students, so I didn’t stand out going to college when I was 44. Also it was cheaper than private universities and colleges, and it was closer to my home at that time.

When did you start Woman Made Gallery and how was it established?

After 4 years of full-time studies at NEIU, my friend Kelly Hensen and I rented a small store-front in 1992 on Chicago’s north side to exhibit work jointly created for our Senior Show. Kelly designed the original hand logo, and also named the gallery ‘Woman Made’ since it was not man-made! We thought that was a clever name for our studio. Then we incorporated and after 7 months Kelly had to leave and Janet Bloch became my WMG partner, and Pamela Callahan joined us. WMG received its not-for-profit status, and we started to charge entry fees for shows and ask for membership support to help us pay the bills.

What does retirement mean to you?

Retirement means less pressure and more time for different things, such as family and making art. I will always volunteer for WMG in whatever capacity I am able to do it. I think I will give one day per week to WMG, 2 days to making art, 3 days to my family, and 1 day for unplanned activities—to explore new things and find time for old friends.

What electronic gadgets do you use?

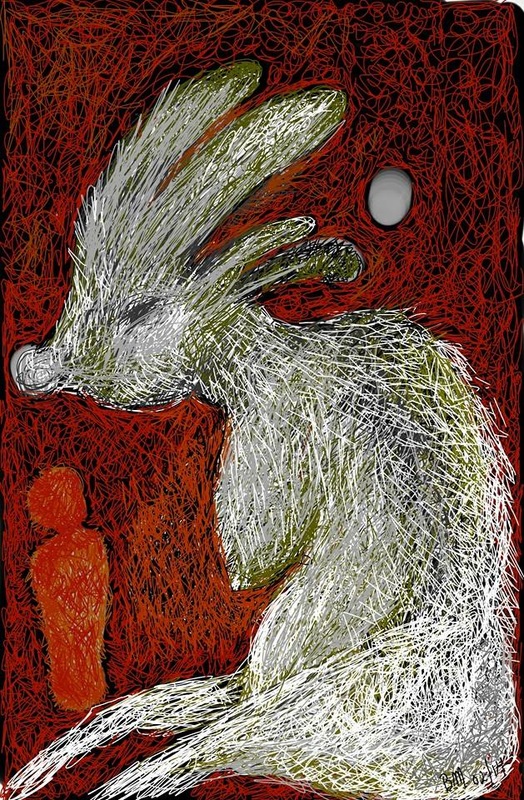

The computer of course, but I use my cell phone for everything, including to create art.

What does feminism mean to you?

Feminism is a tool. It aligns with my beliefs and values, and it helps me to function in this culture, in this world. Feminism means that women deserve to be treated equally in society throughout the world.

Where do you see feminism today and going forward?

Feminism seems to be a complicated word that elicits different reactions. Feminism is a belief that all genders are equal—it is not a bad word. We’re closer to achieving that goal, but there is a backlash now and much work to be done to achieve the goal of equality for all. There needs to be equal pay for equal work. Women should be in control of their bodies and their destinies. Women are sexual beings in their own right, and should not being exploited for their sexuality. Fashion, the beauty industry, and advertising help objectify women. Feminism can help to change attitudes, beliefs, and behavior. Men who are feminists can be of great help to make this world a better place. I am waiting for that.

Have LGBTQ advances assisted feminism?

I think they have helped, and feminism is helping the LGBTQ cause. Collectively they are working on responses to marginalization and oppression.

Will UN Women ambassador Emma Watson’s HeForShe program have an impact in the world?

Yes, because she is a role model for many young women. Our culture is so star-obsessed that any help from those in the limelight will definitely assist the cause, as will the help from men. But action is required and not just the words, ‘I am a feminist.’

What three words describe you?

Outspoken, energetic, creative.

Do you have a mentor?

Yes, Mary Stoppert is my mentor. She was my professor at NEIU and taught sculpture and classes in feminist art. She has influenced me, and she has inspired WMG.

Who have been artistic and feminist influences?

Studying art in Bremen, Germany, early influences were Käthe Kollwitz and Paula Modersohn-Becker. I didn’t even know the word ‘feminism’ before I came to this country in 1965. In 1988, going to NEIU, and having classes with Mary Stoppert set me on my life’s course. I admire the art of many women artists, but the work by Mary Ellen Croteau has always resonated with me artistically and as a feminist.

What has been the most challenging aspect for you at WMG?

It was always a challenge to raise enough money to be able to pay the bills in order to keep Woman Made Gallery going and getting stronger.

What has been your most rewarding or significant accomplishment?

Most rewarding are all the beautiful connections I have made. I know wonderful people, both artists and art-interested. All those people have things in common that I also believe in. It’s truly a big family where everyone is related in one way or another. It’s peaceful and possible.

What would you still like to accomplish?

I’ve never thought about accomplishment, and I don’t have a list. I want to contribute in an area where I fit best.

How would you like to be remembered for your time at WMG?

I hope I encouraged and inspired people. I wanted to make people feel good about themselves and what they do.

Will you continue at WMG in another capacity?

Maybe I’ll take a little break, and then I will volunteer—perhaps invite members to renew their support or help with the annual Gala fundraiser.

What would you like to see WMG achieve?

I would love for WMG to secure enough funding to pay its staff adequately. Running a gallery is a ton of work, but even a labor of love deserves a decent salary.

Also I’d like to see WMG expand to a larger space with enough room for juried and curated shows, an area for its permanent collection, an Artisan shop, an art library, workshop areas, tea-room, and meeting space in an accessible area with plenty of parking.

What is a significant challenge of non-profit organizations?

Funding is a big challenge for most non-profit organizations combined with setting realistic goals and expectations.

What is a key strength/challenge of the Chicago art market?

Chicago’s art scene has great diversity with mostly a down-to-earth attitude. I call it anti-glitz. Maybe if it had more glitz it would be easier to sell art. But I don’t know if that would be a good thing.

Do you see any trends in art?

Not sure. I know so many artists who are creating wonderful work, and all so different from each other. I think ‘unique individualism’ is in and always has been.

What is the good, bad & ugly of being an artist today?

To create is so very wonderful and rewarding, and looking at the art of my ten grandchildren, an inborn activity that many of us, unfortunately, eventually give up. It would be a more peaceful world if we all created art. If pursued professionally, it is very difficult to earn a living making art.

Do you have any advice for emerging artists?

Find your unique voice and vision, and say it well. If you include an echo, acknowledge it.

How do you relax?

I write emails.

If you could have lunch with any artist, past or present, who would it be?

Käthe Kollwitz.

What are you currently reading?

I prefer biographies to novels.

Is there anything else that you would like to say?

Thanks Kathleen, for making me think about myself. It was difficult.

(Kathleen Waterloo had an 18-year career in interior architecture in Chicago. She received her Bachelor of Fine Arts from the School of the Art Institute in Chicago in 1996 and is currently an artist in Chicago.)

'No Sleep Monster' Cell Phone Art by Beate Minkovski